These major infrastructure projects — from Boston to Orange County and from San Francisco to New York – demonstrate how time and money can be wasted and public safety threatened when politics, privatization, and poor decision-making take control.

Indiana Toll Road

A 157-mile stretch of highway running across Indiana from Illinois to Ohio has been privately operated since 2006 when the Indiana Toll Road Concession Co. (ITRCC), entered into a 75-year lease agreement with the state for $3.8 billion. ITRCC filed for bankruptcy after 8 years, due to less-than-anticipated revenue and, it claimed, fallout from the 2008 recession. Private investors, owed more than $6 billion by then, received about 95 cents on the dollar in a 2015 reorganization agreement. Creditors then agreed to lend $2.75 billion to the new private operator. IFM Investors.

Texas Highway 130

This 41-mile section of toll road northeast of San Antonio was built and operated by SH 130 Concession Co. until the operator had to hand over ownership to its lenders in 2012. The company walked away from the operation citing light traffic and heavy debt that forced it to file bankruptcy. Taxpayers, however, took the hit: Highway 130 construction was backed by $430 million in federally-guaranteed loans while Texas received just $3 million of the $25 million it was due in toll revenues under the public-private partnership agreement.

Airport Link (Brisbane, Australia)

Australian media called it “one of the biggest construction project disasters in recent history,” a 4-mile tolled tunnel and road to Brisbane’s airport that failed to carry enough paying traffic to break even. Initial forecasts from the failed project operator, Brisconnection Consortium, predicted the completed Airport Link toll road would attract 170,000 vehicles daily. After opening in July 2012, however, fewer than 50,000 drivers took that route. The operation went into receivership in early 2013 before Transurban purchased it for $2 billion — less than half the tollway’s $4.8 billion construction cost.

South Bay Expressway / State Route 125 (California)

This 10-mile toll road serving the greater San Diego area was supposed to be built for about $360 million through the conventional process, but by the time South Bay Expressway LLC was finished, the cost to private investors and the public had jumped to $893 million. The company fell into bankruptcy three years after opening in 2007. The San Diego Association of Governments — taxpayers — eventually bought the toll road for $341.5 million. The company also defaulted on a $140 million federally-guaranteed loan.

Presidio Parkway

After awarding four competitively-bid contracts to replace the 1.6-mile road, four contracts totaling $473 remained. Instead of continuing with the conventional and less-costly delivery method, the project was turned over to Golden Link Concessionaire as a P3 to complete and then maintain for 30 years. The new single-source, no-bid agreement inflated the cost of the Presidio Parkway project to $1.1 billion plus a $173 million payment for reaching a certain construction “milestone”. While the project was supposed to be built for a fixed price, the developer sued the state and ultimately received more than $100 million extra from settlements. The impact will be felt for years, as $1 billion from state transportation funds will go to pay the private investors for the next three decades.

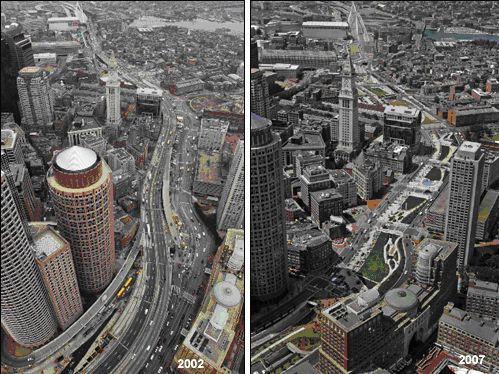

The Big Dig

As the most expensive highway in US history, the Central Artery and Tunnel — known as “The Big Dig” — started as a $2.6 billion Boston project. By the time it was finished, its cost had ballooned to $15 billion, plus another $9 billion in interest. It was completed 8 years late and was plagued with innumerable errors, such as “design blueprints that didn’t line up properly, to the faulty mixing of concrete,” according to the Boston Globe. Most tragically, a ceiling collapse killed a car passenger.

Pocahontas Parkway (Richmond, Virginia)

This 8.8-mile project has the distinction of being the Virginia Commonwealth’s first road built via a public-private partnership — and a two-time loser at privately profiting from public road tolls. Virginia’s Public Private Transportation Act of 1995 breathed life into the design-build Route 895 project to connect two interstates southeast of Richmond. Private debt and taxpayer-backed TIFIA funds paid for the construction. The parkway’s opening rolled out in stages starting in 2002, but traffic estimates that underpinned its toll-driven business model proved too optimistic. By 2004, the private side of the partnership, the Pocahontas Parkway Association, faced bankruptcy. It didn’t even have enough money to pay the Virginia Department of Transportation for the road’s upkeep. The state (i.e. taxpayers) took over the road before signing a 99-year operating lease with Australian-based Transurban. The 2006 agreement included taking on the road’s remaining construction debt and building a 1.5-mile extension to the Richmond Airport. Future development that Transurban thought would grow the toll road’s traffic and profitability failed to materialize. Transurban cut its losses in 2014 and walked away from Pocahontas Parkway. The project’s European lenders have since taken over the road and raised the tolls. The private operators owe VDOT $611 million for the time it ran the parkway.

Riverside Freeway / State Route 91 (California)

A 10-mile tollway built in 1995 and operated under a P3 agreement that gave the private entity, California Private Transportation Company, veto authority over projects that would relieve congestion but might syphon off traffic — and profits — from its toll lanes. The so-called “fixed price” contract was for $57 million, but the actual cost was $130 million. To escape the non-compete clause with the company and regain control of freeway development, the Orange County Transportation Authority — and by extension, the taxpaying public — purchased the road for $207.5 million.